BEYOND THE SCOREBOARD

An occasional sports feature highlighting the unique stories of local athletes.

Football players often arrive at Lackawanna College in need of a second chance. Poor grades may have caused them to be passed over by Division I programs. The young men find structure, support — and for the last 32 years, Mark Duda — at the Scranton school.

The head coach often provides that structure and support before sunrise. He walks the hallways of McKinnie Hall, where his team lives. He blows his whistle to wake his players. Practice starts at 6:30 a.m.

“We're teaching them that we care enough about them to wake them up,” Duda said. “As soon as you find somebody who cares about you, you start to perform better. As soon as you realize that people care what happens, you start to care what happens. And then you get better and better and better.”

Duda, 64, announced this week that this will be his last season as head coach of the Falcons. A recent diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease — which could be the result of his time as a defensive tackle in the NFL — is forcing him to slow down.

There has never been a football snapped at Lackawanna College without Duda being part of the game. Over three decades, 450 Lackawanna players have transferred to Division I football programs. Twenty-five men later played for the NFL. Duda has more wins than any other active coach in the National Junior College Athletic Association.

He gathered the team Monday morning. The news of his diagnosis and plan to retire made many of the young men cry.

“They all have a future here, and a really bright one, and the school has a bright one. But they have to understand that I can only last so long, and then inevitably, there has to be change,” Duda said. “It was one of the hardest things I've ever done.”

Helped save Lackawanna

Duda grew up in Plymouth, the son of Leonard and Margaret Duda. At the age of 10, he told his dad he wanted to play in the NFL. His dad told him he’d need to work hard, and each year his parents would buy him weights for his birthday. Duda’s father died last year, and his mom died on Sunday — which Duda also told his players during Monday’s meeting.

At Wyoming Valley West, Duda served as a major part of the "Mad-Dog" defense that helped the team go 9-2 in 1978, his senior year. He received a scholarship to play football at the University of Maryland, where he recorded 13 sacks in his senior season, a school record that stood until 2015.

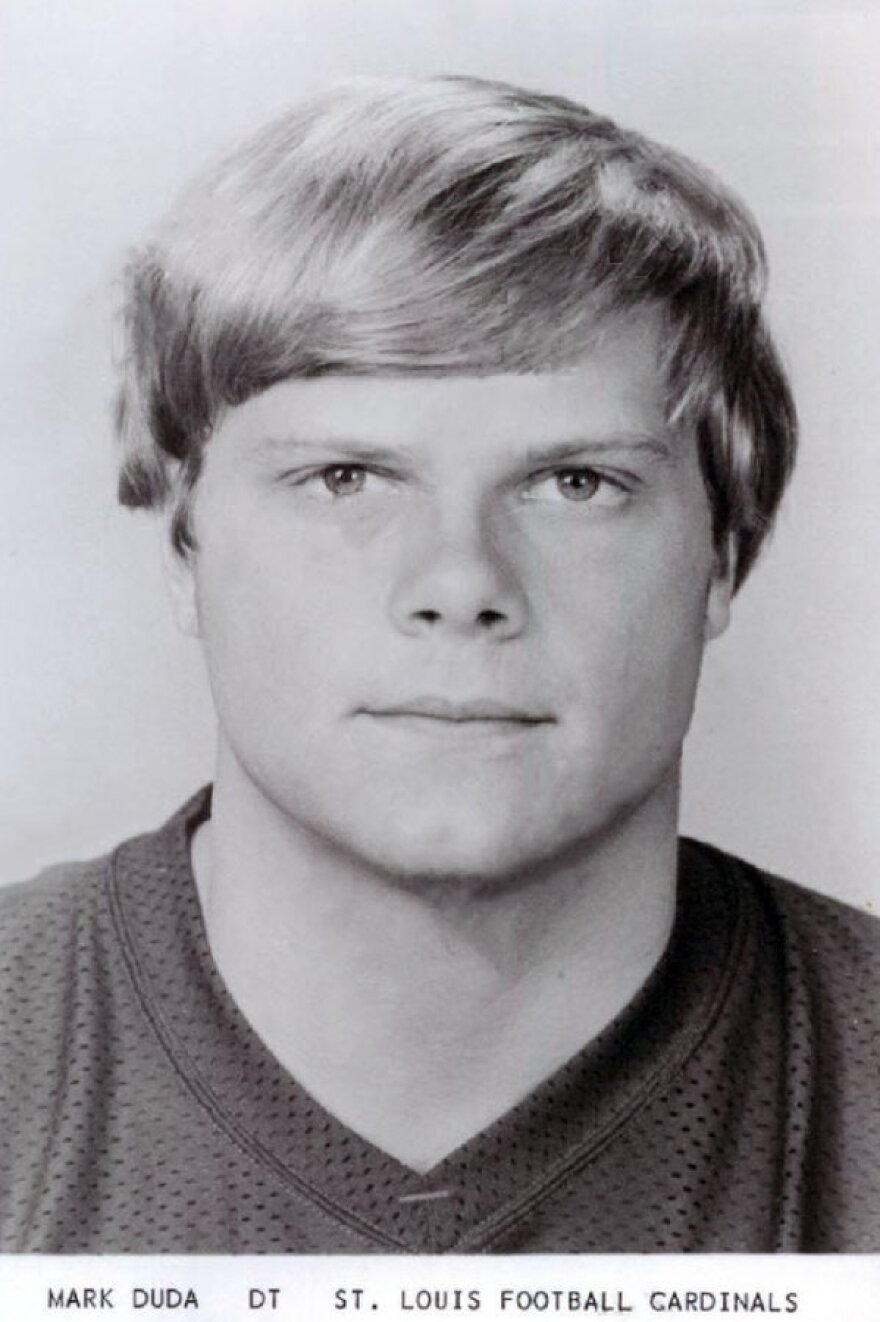

The St. Louis Cardinals drafted Duda in the fourth round of the 1983 NFL draft. Duda made 34 starts and played in 55 games, recording 9.5 career sacks during his five seasons. He returned to Northeast Pennsylvania, earning a degree in education from East Stroudsburg University in 1991.

When Lackawanna College started its football program in 1993, Duda served as the new team’s defensive coordinator. He took over as head coach the following year.

“When you think of Lackawanna, the first thing you think of is Mark Duda,” said Paul Wiedlich, an assistant coach who focuses on the linebackers. “He’s really a truly great coach, but even a better human being, the most humble guy I've ever met in my life.”

Duda helped establish the team when the college greatly needed the enrollment boost. College President Jill Murray credits him for helping save the struggling school, then known as Lackawanna Junior College.

When Duda became head coach at Lackawanna, he thought he’d stay for a bit, until an offer from a bigger school came along. But at Lackawanna, he found his home. He met his wife, Denise, at the college. Their daughter, Taylor, grew up on the sidelines. He turned down numerous unsolicited offers to coach elsewhere.

“We're lucky to have had him for so long. And I also think, as much as his football knowledge is incredible, his people knowledge is equally as deep. He gets people, he gets kids, he gets students … He teaches these kids not just to be students, but to be good young men, to be good citizens, for some of them, to be good dads,” Murray said. “You see that over and over and over, generation after generation. Their lives are changed because of Mark Duda.”

A light rain fell as practice ended this week. The Falcons, 4-4 this season, face Georgia Military College at home on Saturday. Duda blew his whistle, and the team huddled at the 50-yard line.

“He's a father figure to the players. He's a coach, he's a mentor. You can just talk to him about anything in life,” said Kevin Roginski, an assistant coach. “He's a guy you want to get down with and go into battle with. No matter what, he's leading the charge.”

Providing structure, support

The team had schoolwork to get done that night, before another 6 a.m. whistle wake-up from Duda or one of his assistants. Being part of Lackawanna’s football team means adhering to a strict schedule.

Many of the players struggled academically in high school. The football program gives them extra help — and holds them accountable for grades. Duda wants to prepare the team for whatever comes next — transferring to another school, entering the NFL or earning a degree and finding a job.

“We have to make them understand how important it is to get where they need to go,” Duda said. “What happens is they miss less and less and less things, and then pretty soon they start going to every single class. And then now, if you go to every class, you usually do pretty well.”

Michael Johnson walked off the field after practice. He felt lost after high school. The Ontario native, who played high school football in Harrisburg, wasn’t sure where to go or what to do. Duda encouraged the linebacker to come to Scranton.

“Coach Duda means everything. He's been just a pillar of hope to lean on. He's been so positive, just strong willed,” Johnson said. “He's everything what I imagined having a head coach (would be like). He's just been it. He's been here for us, on the field, off the field, just helping us take care of everything … It's just really hard seeing someone like that retire, because he gave me a really, really big opportunity that I'm gonna remember for the rest of my life.”

Michael Odeyemi played high school football in Reading and now plays on Lackawanna’s defensive line. He hopes to transfer to a Division I program, and then play in the NFL. He’d also like to be an architect.

“Coach Duda is a father figure to me,” Odeyemi said. “He is the person that we go to for everything that we need. You need help with schoolwork. You need help with anything… He always helps us with everything.”

Link between contact sports, Parkinson's disease

Duda noticed something might be wrong in the last year. His finger would move involuntarily. His back muscles became so tight he could barely move. His doctor suggested he see a neurologist.

Specialists diagnosed him with early stage Parkinson’s disease in February. The progressive neurological disorder affects movement, balance and coordination. Fatigue is a common issue with Parkinson’s, and stress can make it worse.

“I knew that my days of coaching at this level were going to be done,” Duda said.

Doctors believe Duda’s time in the NFL may have contributed to his diagnosis. A 2020 study found that having a single concussion increased the risk of developing Parkinson's disease by 57%. Having multiple concussions further compounds the danger. Pro Football Hall of Fame quarterback Brett Favre revealed he had Parkinson’s last year, bringing more attention to the link between contact sports and neurodegenerative diseases.

For now, Duda feels well. Doctors can’t tell him how fast symptoms will progress, but he’s doing what he can to stay strong and healthy.

“At least I know I've played a game that I loved, I've coached a game that I have loved. And if that's how it ends at the end of it, then you know, so be it,” he said. “You’ve got to look at it from the positive side. If you get negative about this, you're never going to make it.”

Taking lessons to the NFL

Mark Glowinski wanted to play football after graduating from G.A.R. Memorial High School in Wilkes-Barre in 2010. He decided to play for Duda, a “local hero” who grew up on the other side of the Susquehanna River in Luzerne County from Glowinski. Duda went Division I, he made the NFL. Glowinski wanted to be like him.

“If I just listened and gave my best effort and actually listened to the things that he was talking about, then at least he’d give me an opportunity, a chance,” Glowinski said. “Coach Duda gave me a chance to be on the team, and I think it was one of the most pivotal moments, and pretty much led me to where I am today,”

After his two years of football eligibility at Lackawanna, he transferred to West Virginia University. The Seattle Seahawks selected the guard in the fourth round of the 2015 NFL draft. He’s now a free agent, after stints with the Seahawks, New York Giants and Indianapolis Colts.

The longer he stays in the NFL, the more he realizes the impact those two years at Lackawanna made on his life. Duda pushed him hard, from being ready for early morning workouts to finding discipline and determination in the classroom.

“I feel like there was more knowledge and life lessons and different things, the hard times and just great times. I felt like we were a family. The team was like glue,” Glowinski said. “We wanted to make sure that everybody succeeded within the family, and we did everything that we could to make sure that we were giving ourselves the best opportunities … there's a reality that not everybody's going to go Division I or play in the NFL, but at least it was the opportunity to continue and better themselves.”

Humbled by appreciation

After stepping down as head coach at the end of the season, Duda will remain at the college part-time and serve as an athletic adviser. He’ll help the school transition to Division II athletics next year and become part of the PSAC, the Pennsylvania State Athletic Conference.

Lackawanna dropped the “Junior” from its name almost 25 years ago and began offering bachelor’s degrees in 2017. Over the last decade, undergraduate enrollment has increased by 30%.

As part of Division II, players will have four years of eligibility at Lackawanna, instead of two with junior college division sports. That will provide more chances for teammates to learn from one another, with upperclassmen being able to serve as role models for younger players, Duda said. That also will give the program a longer chance to make an impact.

Duda won’t be there on the sidelines of every game, in the locker room after a tough loss, or be the one blowing the whistle at 6 a.m.

The rain starts to fall harder as he walks off the field at practice this week. He glances at his phone. He keeps in touch with many former players regularly, but after his retirement announcement, he’s been overwhelmed — and humbled — by the response.

A player told him he’s an engineer now. A teacher told him he teaches his students the same lessons he learned from Duda.

“A lot of those people just needed us,” Duda said. “When we were here, they needed us, and so we're here for them, and I'll never forget them, ever — no matter how long I live.”

WVIA profiled Duda as part of a 2022 VIA Short Takes. Watch below.