In 2001, James Snee was healthy and ready to start a family with his wife.

Then, routine blood work came back positive for leukemia.

Snee needed a bone marrow transplant to save his life within weeks. None of his family members were a match, but a stranger in Texas was.

“I let him know that I'm alive 24 years later, in large part because of him,” Snee said. “My kids exist in part because of him, because we had kids post transplant, so I wouldn't have been around to father those twins.”

'The difference between life and death'

While Snee does not know his donor's identity, he knows he was a part of NMDP's bone marrow registry. The organization formerly was known as the National Marrow Donor Program and Be the Match.

Snee credits NMDP and its role in finding him a donor with saving his life.

“I would not have lived,” Snee said. “It's literally the difference between life and death for people all over the world.”

Joining the registry takes about five minutes. All it requires is a cheek swab and filling out a short form that sends an individual’s personal information back to NMDP.

If someone is a match for a patient, NMDP will call them. Most donors only have to give blood. Some have to go through a minor operation to extract bone marrow. Either way, NMDP pays for travel, lodging and missed days of work.

Athletics and bone marrow registration

Snee now volunteers at bone marrow registry drives hosted by local football teams. Previously, he’s worked with King’s College. This year, he helped Lackawanna College’s football team get their drive off the ground. He left the event an hour before it was over, but by then, about 70 people registered.

“You don't know how many people on there might one day get the phone call that they've saved a life because of a little bit of effort on our part,” he said.

After registering for the bone marrow registry, an individual will stay on it until they are 61 years old.

NMDP realized that officially partnering with football teams could help bolster the younger end of the registry after Villanova University's former head football coach Andy Talley got his team involved for community service in 2008.

The football team model quickly spread across the country after that. Other athletic teams even host the drives now.

Houston Roberson, a community engagement and events coordinator at NMDP, said partnering with college athletics has become an important part of the organization’s programming.

“We want young people that are willing,” Roberson said. “They're healthy — 18-40, that's when you're kind of your prime, and you're not yet experiencing too many health issues. When you join the registry, if you join [and] you’re 20, you may not get called until you're 50.”

Ronald Francois from NMDP said that the partnership has grown to more than 300 college athletic programs across the country.

Francois said finding a match is incredibly difficult and that 70% of people looking for a match do not find one within their families. More people on the registry means higher chances for those looking for a match.

There also needs to be an ethnicity match from donor to patient.

“We serve a very diverse ethnic population,” Francois said. “Because our registry to date is about maybe 40% ethnically diverse, we're really trying to help raise the awareness and add more to our registry to provide the outcomes for everyone.”

Snee noticed a larger turnout to swabbing events this year than in the past. He thinks there’s more awareness as people do their part to help Eddie Kaufman, a 20-year old Mid Valley High School graduate recently diagnosed with leukemia. Kaufman attends Roanoke College, where he is a sophomore and played both golf and baseball before his diagnosis.

“Eddie, he's 20 years old, he is the picture of health, a college athlete,” Snee said. “He has found on the donor program a 9 of 10 match, which means 9 of the 10 markers they look for completely matched. They're doing all of these drives in the hopes that they could find a 10 of 10 match, because the closer you are to a perfect match, the higher the predicted rate of success.”

Wilkes football encourages registration

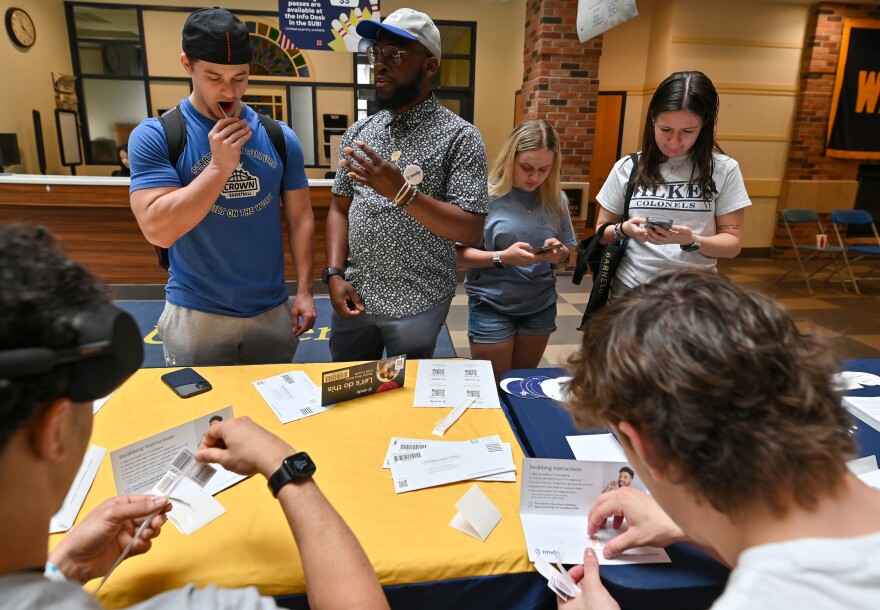

Wilkes University's football team hosted a registry drive on Friday, April 25.

Members of the football team ran around campus with signs, capes and superhero masks, trying to get other students to join the registry.

They held signs from NMDP that said, "The power to save lives is in your hands" and "Swab to save a life."

Signs at the swabbing stations included Kaufman's information so students could see the local impact of joining the registry.

Sophomore student-athlete Anthony Torres already joined the registry before he took to campus to encourage others to do the same.

“We're trying to make a change,” Torres said. “We're trying to help save a life. We're bringing a voice for a lot of people that don't have their voice.”

Chris Bantell, the team’s associate head coach, encourages his players to give back.

“It's really important for the student athletes,” Bantell said. “We can expose them to some of these opportunities where you're able to better your community. Don't just be a member of it, be a leader in your community. It's almost like a duty, so that's been our big push to them.”

Elias Dixon-Glibert, a freshman from Maryland, said he’s glad his coaches encourage community service, so he can learn more about his new home outside of football and schoolwork.

“I think that goes to show that as a team [we] really care about Wilkes Barre, and we actually want to be involved with the community,” he said.

Wilkes student Kaylin Zelinski joined the registry as she walked past the football team’s tent on campus.

“If my bone marrow can help anybody, I'm more than willing to give it up,” Zelinski said. “What do I need it all for?”

Zelinski did not know about the bone marrow registry before she was flagged down by the team. She hoped other students would take the quick detour to join.

“It was the quickest thing ever,” she said. “If they were interested, I would encourage others to do it.”

Torres hopes other young people realize how important their participation is in saving lives around the world.

“Hey, we all deserve to live,” Torres said.