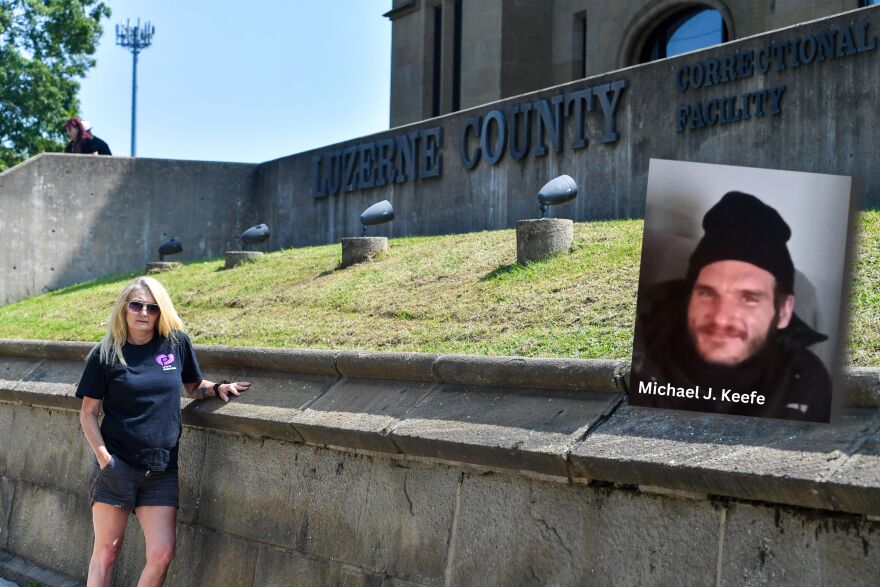

Michael J. Keefe took methadone for nearly six months prior to his detention at the Luzerne County Correctional Facility (LCCF) in mid-May. The thirty-seven-year-old had tried other addiction management medications in the past.

FDA-approved methadone was “the only thing that worked” to relieve his cravings and get him off the synthetic opioid street supply, he said.

But Keefe says he was cut off from methadone in prison, suffered multiple seizures and was transported to Wilkes-Barre General Hospital before returning to his cell. He was still waiting for his prison sentence close to two months later.

“I’m afraid I’m gonna die in here,” said Keefe, tearing up during an in-person visit earlier this summer. Dressed in a dark green county-issued prison uniform, he had a newly-shaved head and spoke via phone through a glass partition.

In the two weeks after incarceration, Keefe went through withdrawal from prescription methadone and complained daily to medical staff, he said. WellPath, the company contracted to provide prison medical care for the county, later started Keefe on Subutex — a brand name for buprenorphine or “bupe” — an addiction medication he previously tried and discontinued while out in the community.

Providers often wait until opioids or meds like methadone have fully left a person’s system before starting a patient on Subutex or naltrexone, another opioid addiction medication, treatment coordinators say. Otherwise, patients could be sent into a state of precipitated opioid withdrawal that can cause vomiting, diarrhea and body aches in the hours after they start taking buprenorphine.

In rehab settings, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) notes this waiting period is often medically supervised with other drugs prescribed to limit the side effects of severe withdrawal.

In Luzerne County prison, Keefe said Subutex didn’t make it any easier to sleep, eat or stop feeling tremors. The county withholding methadone violates his rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), he said.

For their part, Luzerne County prison officials say WellPath does give methadone to its patients. In addition to Subutex, the prison also offers naltrexone, another long-lasting opioid addiction medication that patients must wait to take after withdrawal.

“Methadone is offered when it is determined that is the best treatment option per the medical team for Medically Assisted Treatment of an inmate. WellPath contracts with Comprehensive Treatment Center of Wilkes-Barre to provide Methadone,” Luzerne County Prison Warden Jim Wilbur said in an emailed statement.

But Wilkes-Barre Comprehensive Treatment Center clinic director Kelly Ormando said LCCF only uses her methadone clinic to treat pregnant inmates.

“I would like to partner with [the prison] in the future” to expand access, Ormando said, but couldn’t say whether any plans were in the works.

Neither Wilbur nor county Manager Romilda Crocamo responded to follow-up requests asking who makes treatment decisions for inmates – whether it be WellPath, a methadone clinic, prison officials or county government.

Crocamo insists the county is abiding by ADA obligations.

In late July, the U.S. Department of Justice held a virtual training for Pennsylvania prison and jail employees about prisoners’ addiction medication rights.

“Several [LCCF] staff members attended,” Crocamo said in an email, adding: “I am pleased to inform you that we are doing everything recommended.”

But Crocamo again did not respond when asked if inmates who received methadone while out in the community are provided the same medication at LCCF.

Dangerous gaps in care?

Providing only some — but not all — addiction medications still leaves dangerous gaps in care, according to advocates. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) varies widely at county facilities across Pennsylvania, and the state Department of Corrections has little oversight on county prison decisions, according to the DOC.

Prison and recovery advocates say change is slowly coming via legal pressure, as some county prisons that previously provided methadone only to pregnant people are being hit with notices from the U.S. Department of Justice.

The Pennsylvania Institutional Law Project has represented clients for methadone denial in prison, including in Delaware County.

In recent years, Luzerne County settled for hundreds of thousands of dollars with families related to deaths at the prison. Advocates say several suicides at LCCF were driven by symptoms of synthetic opioid withdrawal. They say withdrawal is more dangerous now due to drug combinations including fentanyl and sedatives like xylazine and medetomidine.

“You have bad dreams. It’s like the devil is with you,” said Kimberly Wills, Keefe’s former drug counselor at Wilkes-Barre Comprehensive. Your thoughts can easily turn to “my family would be better off without me,” she said.

The Justice Department last year secured an agreement with Allegheny County after an investigation found its facility didn’t offer methadone to prisoners who should have received it. Other facilities have taken note and voluntarily adopted policies.

For example, Lackawanna County, which also contracts with WellPath, will keep any inmate on methadone if they arrive with a valid prescription, said Warden Tim Betti. This year Lackawanna also was one of several counties ordered by the Department of Justice to review its addiction med policies based on alleged discrimination in recent years.

Recent Luzerne County Council meetings indicate LCCF may soon incorporate extended-release injectable buprenorphine, or Sublocade, which is typically not used for opioid withdrawals. In July Council approved more than $600,000 in opioid settlement funds for the medication.

Keefe sent to Lackawanna County

Keefe says he filed several complaints with Luzerne County prison officials and medical staff after they did not give him prescription methadone.

Weeks later, after stints at a hospital for seizures, Keefe was transferred from Luzerne County Correctional Facility to Lackawanna County Prison. The move was based on “a warden’s agreement,” according to Keefe’s parole officer, Bianca Alberola, during a sentencing hearing on July 17.

Because Keefe was denied methadone in Luzerne and instead started on Subutex, his family says Lackawanna could not begin a methadone plan.

WVIA News filed a right-to-know request for Keefe’s prison records while incarcerated in Luzerne County. The county said, “Keefe did not file any formal grievances.” Officials would not share details of disciplinary or medical records, citing internal document policies that prevent them from discovery. Housing records and details of Keefe’s transfer were forthcoming in late July, an open records officer said in an email.

An LCCF housing document provided Friday offered only basic details about locations in the facility where Keefe was housed between May 17 and June 20, save for a May 23-27 absence. As noted above, Keefe said he was taken to the hospital during his stay, though he didn't recall dates.

The document does not speak to his transfer or his medical care, other than noting an infirmary stay between May 17 and May 20.

State vs. county policies

While LCCF is one of many county prisons statewide that doesn’t offer methadone to people who once received it in the community, tracking county policies proves difficult, said Steven Seitchik, statewide medication-assisted treatment (MAT) director with the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections.

Methadone, which was approved to treat opioid addiction starting in the 1960s, is one of three meds used by the state prison system to treat opioid use disorder, including buprenorphine and naltrexone, Seitchik said. Those three medications were all suggested in the DOJ’s July training to Pennsylvania prisons.

“There have been several legal cases across the country looking at the Americans with Disabilities Act,” he said. “So the legal precedent… is that if someone comes in on a verified prescription, you need to keep them on that prescription while they're incarcerated.”

Seitchik has shared state MAT guidelines with county prisons, whose officials can then decide to implement, "tweak it or throw it in the trash can,” he said. But county jails have their own “logistical challenges” related to treatment.

“People come and go rather quickly at the county level and release dates can be very, very tricky. It may not be clear whether the person is leaving in a day, a week, a month or a year," he said.

Still, Seitchik said, some counties “will make it appear that they offer all three medications when in fact they only offer methadone to pregnant inmates.” When officials are asked whether the policy benefits all prisoners, “then the answer almost always is no,” he added.

Northeast Pa. county prison MAT policies

A patchwork of medication-assisted treatment policies exists in the region’s county prisons.

Next door to Luzerne, Columbia County Prison policy says if an inmate’s methadone prescription is verified, they are transported to Watsontown Treatment Center “as soon as possible” for “guest dosing,” then returned to prison with additional doses for the rest of the week. Each week, the prison repeats this process for methadone dosing. In other cases, if deemed appropriate, Suboxone, a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone, must be administered as a pill and crushed to dissolve under the patient’s tongue

Carbon and Pike counties contract with PrimeCare, but prison officials say they are not certified opioid treatment program providers. Intake screenings are conducted by Carbon Monroe Pike Drug and Alcohol counselors. PrimeCare documents obtained in a right-to-know request offer a vague look at addiction treatment care:

“If a patient comes in on [addiction] medications and the facility does not have a MAT program in place, these patients need to be detoxed appropriately. They need to be seen by the provider, and, said provider, knowing the capabilities of the site, needs to evaluate and determine if detox is to be continued or if MAT is to be started. Consider the efficacy of MAT and length of incarceration.”

In Monroe County, which also contracts with PrimeCare, prison Warden Garry Haidle said the prison does not have a program for opioid addiction meds. Susquehanna and Sullivan counties also have no prison MAT programs, according to officials there.

Wyoming County also contracts with PrimeCare, but provides Subutex to inmates who were prescribed the med in the community. Documents in Wyoming say “the provider may opt to utilize MAT-related medication to assist with a medically supervised withdrawal protocol, such as the methadone or buprenorphine taper.”

Officials say Lycoming County Prison coordinates with River Valley Health to provide naltrexone to inmates. In Bradford County, protections are offered to pregnant inmates for opioid addiction meds, as long as they were “in good standing” with the program before incarceration. “[For] the protection of the unborn child she will be allowed to continue MAT,” according to Bradford County Correctional Facility policy and procedures.

As of 2022, Wayne County only provided naltrexone and Schuylkill County only gave addiction meds to pregnant inmates, per Pa. Institutional Law Project. Prison officials in Wayne and Schuylkill could not immediately be reached for comment on policy updates.

Longer prisons sentences, better care

Wills, Keefe’s drug counselor prior to detention, was formerly incarcerated in federal prison and refers to herself as “an addict in recovery.” She said the irony is that crimes sending people to state and federal prisons often result in better addiction management care.

If someone’s sentence is more than one year, they’re sent to a state prison, she said. With a shorter sentence, they’re remanded to the county jail.

When Wills’ state prison clients leave detention, they enter rehab facilities that coordinate with the Department of Corrections, she said. Then from rehab, they move into a halfway house.

Her clients from county jails, however, often relapse and begin using street drugs back in the community.

“So state and federal [prisons] do have great programs, but the county does not,” she said. “A lot of these addicts are only doing county time, and they’re going back into the environment and they’re dying. We’re losing so many people.”

‘Broken system’

Keefe has cycled in and out of Luzerne County Correctional Facility. He’s committed several non-violent crimes related to drug possession, trespassing, and retail theft, according to state court records that date back to 2013.

In a July 17 sentencing hearing for a parole violation, Luzerne County Court Judge David Lupas said Keefe’s record over the last decade means this time, he should spend eight to 23 months at the county prison.

His first two months were served in Luzerne, and the remaining time will be in Lackawanna. Keefe is eligible for release on Sept. 16 — four months or half of his minimum sentence — when he would again be required to report to a reentry service center each day. That could pose problems, his family says.

His sister, Pam Keefe, said he never should have ended up in LCCF this time around. He was scheduled to enter an inpatient rehab facility in Hazleton the week of his arrest. She cites the statewide Law Enforcement Treatment Initiative, adopted in dozens of counties, that’s meant to send people to treatment instead of prison. Luzerne joined LETI in February 2023.

In mid-May, Keefe’s ankle monitor died and stopped transmitting his location. Parole Officer Alberola told Judge Lupas that Keefe had stayed overnight at unapproved locations. His family says Keefe was intermittently homeless, but an apartment was waiting for him after rehab.

The day of his arrest, “ClearVision [in Hazleton] had an open bed,” Pam Keefe said, adding that Alberola canceled the rehab request and ordered him jailed. Alberola did not return a call seeking comment.

Had Keefe been arrested in Lackawanna County instead of Luzerne, he would have continued to receive methadone, a fact that angers his family. Both counties contract with carceral healthcare provider WellPath.

“There’s no communication,” Pam Keefe said. “It’s broken, it’s a broken system.”

“There’s no excuse why methadone is not at the jail.”

Editor's Note: Reporter Tom Riese began researching and writing this story at WVIA News earlier this year. He is now a reporter with Pittsburgh affiliate WESA.