When a local bottled water company drew down its well in 2014 near the Barton Brothers Property in Covington and Clifton townships, Round Swamp went dry, Wendy Bolognesi remembered.

“This whole swamp was like the water had just been sucked out of it. I had never seen anything like it,” said Bolognesi. Her family has owned the 772-acre property since the early 1900s.

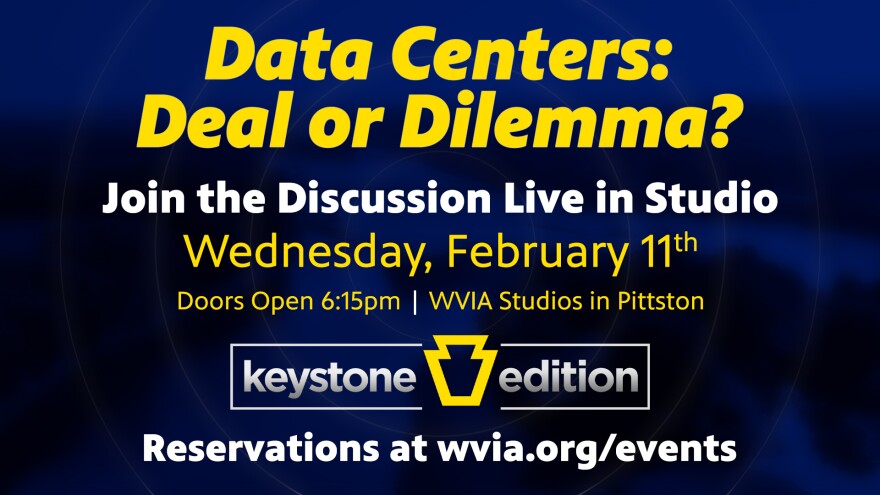

DATA CENTERS:

DEAL OR DILEMMA?

This three-day WVIA News series focuses on data center developments in Northeast Pennsylvania and how they could affect area communities.

● TODAY: What are data centers? Potential impacts on water supplies.

● THURSDAY: How data centers will affect energy grid, prices.

● FRIDAY: How communities are reacting, from protests to zoning regulations.

The swamp is saturated again. A natural spring bubbles up through sand from the ground. Canteen cups hang from a nearby tree. Bolognesi and relatives, Thatcher and Walter Barton, filled the cups and drank the water straight from the earth.

They are three of 13 members of the Barton Brothers Partnership that owns the property, which has two swamps, considered moss bogs, that are fed by underground springs.

The family worries the swamps could run dry again if a data center campus is built on adjacent sites that border the property on three sides in both townships.

According to a lawyer for Doylestown-based developer 1778 Rich Pike LLC, the center’s operator plans to truck in water for cooling computer servers on the 11-building campus.

Attorney Matt McHugh, from Klehr Harrison Harvey Branzburg LLP in Philadelphia, says his client's plans for the campus, dubbed “Project Gold,” have changed since they were first introduced.

"Some of it's in order to address concerns that we heard,” he said. “I think they [Clifton and Covington Twp. supervisors] kind of held us to that standard … of coming up with a plan that addresses concerns they were hearing as well,” he said.

The LLC has an end user for the site, but McHugh said he cannot identify the user at this time.

While residents fear the large nondescript buildings will degrade their communities, developers market data centers as being able to reinvigorate communities, increase tax bases and create jobs.

But Bolognesi and her kin aren’t convinced the complex will be beneficial for this rural corner of Lackawanna County, where a rustic cabin looks out over the property off Clifton Beech Road that their family has enjoyed for six generations.

"People come here for this, not for a data center. And the data center’s negative impact cannot be measured in economic benefit,” Walter Barton said. “It's so destroying the environment, the health and safety of the area.”

"To me, this is sacred ground,” Bolognesi added.

The North Pocono region is one of many local areas where tensions have been running high between residents, local governments and developers. Northeast Pennsylvania has become a hot spot for data center proposals, with over 20 campuses currently planned for the region.

This is the first part of a three-day WVIA News series exploring the growing industry and the concerns raised by communities surrounding data center development.

The series begins by looking at what data centers are, how they operate, and their potential impact on water resources — one of the main issues raised by members of the Barton Brothers Partnership.

Data centers: What are they? How do they work?

Inside the centers are the brains of artificial intelligence, like ChatGPT, cloud services, financial and medical information -- basically anything that’s done or saved online. Those brains are stored in rows and rows of servers stacked on racks.

"Data centers are everything we do every day. It's how we work, it's how we learn, it's how we communicate, it's the things that help us relax online, like streaming videos and social media,” said Dan Diorio, a Poconos native and vice president of state policy for the Data Center Coalition, a national trade association for the industry.

“But it's also just the essential functions. It's financial services, payment processing, electronic healthcare records, 911, geolocation services, state and local governments, and national security. You know, you name it, basically anything and everything requires digital infrastructure these days,” Diorio said.

CLICK TO VIEW MAP:

Pennsylvania Data Center Proposal Tracker, created by NEPA Native Emilia Doda: https://www.padatacenterproposals.com/

Data centers are not new, but they are changing rapidly as the demand for digital storage grows. That means the buildings are getting bigger and consuming more energy.

When a user asks the chatbot to come up with a recipe using random items in their pantry, ChatGPT draws its answer from information stored in data centers.

Move money from a savings account to a checking account to fund an unexpected but much-needed pair of shoes, and that transaction is processed through a data center.

Want to upload a cat photo to the cloud? The cloud is actually located in the servers housed in over 5,000 data centers in the United States — more than any country in the world, according to a Brookings report.

Data centers often store the same information multiple times, and companies often pay to rent space inside them. Larger companies, like Amazon Web Services, operate their own data centers.

Data centers are a 24/7 operation, and the information stored in their servers has to be available at a moment’s notice. If a data center in Virginia goes down but someone in Pennsylvania still wants to watch a movie on Netflix, that’s now drawn to a TV screen from another data center somewhere else — say, for example, Texas.

The infrastructure required for such an extensive service runs hot.

A single data center can consume an average of over 300,000 gallons of water each day for cooling, which is equivalent to the water use in 1,000 homes, according to the Environmental Law Institute.

“These trends raise serious questions and concerns about long-term water availability, infrastructure resilience, and the communities living alongside these operations,” according to an institute report.

Data centers and water use

In 2023, the country’s data centers directly consumed about 17 billion gallons of water, according to estimates in a 2024 Berkeley Lab report commissioned by the U.S. Department of Energy.

Hyperscale data centers alone — which are acres large and house thousands of densely packed servers on multiple floors — are expected to consume between 16 billion and 33 billion gallons of water annually by 2028.

But Diorio from the Data Center Coalition said it’s important to put those figures into context against other water users.

"Data centers use less water than golf courses. Data centers use less water than manufacturing facilities. Data centers use less water than food and beverage production,” he said. “We know that in Virginia, which is the largest market in the world, 83% of data centers use as much, if not less, water than a large commercial office building.”

Diorio’s group is made up of 40 members who are data center owners and operators, who he said, are developing digital infrastructure and building out data centers throughout the country. Diorio pointed to what he sees as misperceptions about how much water data centers use.

"I think it's easy to see some large numbers and think ‘oh, that really looks like a lot,’ but when you compare it across industries, it really shows that the data center industry is a very efficient water user,” he said. “That being said, the industry is actively deploying advanced cooling technologies that help reduce water footprints.”

A river runs through NEPA's data center proposals

The Susquehanna River Basin Commission is tracking data center developments in Pennsylvania. They don’t know how many will actually come to fruition, said Andrew Dehoff, executive director of the commission.

"People, whatever they know of them, they just know they're a big box that drives a lot of computers and uses a lot of energy and don't always think about water,” Dehoff said.

Dehoff said the amount of water data centers actually use can vary widely.

"We have found that some proposed facilities intend to use a lot of water for cooling. But at the other extreme, we've found some facilities that intend to use technology for cooling that has very little water demand,” he said. “We have found that it changes constantly, not only from one facility to the next, but even as a facility goes through the stages of development, we have seen them start off with anticipating high water demand and then making some different decisions and ending up with the lower water demand, or very low water demand.”

SRBC manages water supplies and water flows for New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland for the river’s watershed. The commission oversees large withdrawals from streams, the river and groundwater wells, including consumptive use of water.

"That's water that's withdrawn and not returned, either because it's evaporated for cooling or because it's mixed [for] ingredients,” he said.

Any activity that involves water use or large industrial facilities, like the nuclear power plant in Salem Twp., Luzerne County, and its soon-to-be neighboring Amazon Web Services (AWS) data center, needs withdrawal permits from the commission. SRBC has granted AWS a permit, Dehoff said.

Dehoff believes Pennsylvania could accommodate either many data centers using minimal amounts of water or a few using a lot of water, or some mixture in between.

"But our concern is that it's happening so quickly, right? You know, is everyone on top of it? Is everyone making, you know, the best decisions?” he said.

North Pocono’s natural features

The groundwater from the Barton Brothers Property is unique, Walter Barton said. They are at the top of the mountain, so it’s part of both the Susquehanna and Delaware River basins.

Silver Creek and Ash Creek run through the property. Both, like many streams in the Poconos, are considered exceptional value (EV) waters and class A trout streams, which means there is enough of the fish living in clean water to sustain natural wild trout populations. The creeks were designated as exceptional value waters in 2015, Barton said. That classification is given to streams in Pennsylvania that have the cleanest and highest quality of water, according to PennFuture. The waterways are also tributaries of the upper Lehigh River, which is part of the Delaware River Watershed.

"It's things like this that feed our entire freshwater ecosystem,” Thatcher Barton said.

With the data centers proposed so close to the property, the family fears the natural beauty that they are now stewards of will be destroyed.

"I've been coming here all my life, and the more that I learn about this surrounding area is that it's very unique in the sense that we still have a lot of really, really important, diverse habitat for stuff like that. And there's not a whole lot of that left, so it's certainly worth protecting,” Thatcher Barton said. "Even without challenges like this data center, we're fighting to do what we can as individuals to try to protect the health of the forest, because forests everywhere, especially in this region, are really threatened. So we need all the help we can get."

McHugh said he was not involved in the site selection process for Project Gold but that it was chosen for the proximity to power and land availability. 1778 Rich Pike has sale agreements with seven property owners — four in Covington and three in Clifton.

Private well users are concerned about data centers

The majority of Covington and Clifton residents rely on well water, wells that they do not want to dry up to cool down servers in data centers.

"Something like this project that could really devastate our water table is, is the last thing we need,” Thatcher Barton said in August.

On Friday, McHugh said that the end user of 1778 Rich Pike’s development will truck water in for the cooling required at the centers.

"We're not going to use groundwater well water to cool the data center equipment, and we've agreed that it will not come from any wells,” he said.

A centralized well system will be used for sinks, bathrooms, drinking water, and humification, McHugh said.

There are more than one million private water wells in Pennsylvania serving about 3.5 million people in rural areas, according to PennState Extension.

The North Pocono residents are not the only ones concerned about well water usage. Residents in Sugarloaf Twp. in Luzerne County are also mostly on wells, and there is a data center proposed for neighboring Hazle Twp. in the Humboldt Industrial Park.

Pennsylvania Glacial Till LLC, a New Jersey company, has proposed constructing an eight-building data center campus on 100 acres in nearby rural Tobyhanna Twp. in Monroe County. The campus could be built on Caughbaugh Road off Route 115. The community is mostly on well water.

Tobyhanna Township Residents Against Caughbaugh Data Center hired a lawyer. They are challenging the supervisor's data center overlay zoning amendment, which was passed in December, for the property. The residents are raising a substantive validity challenge to the ordinance, saying it allows for "unlawful spot zoning."

Groundwater systems can start at most shallow depths beneath the earth, anything from five to 10 feet below, to more significant depths, said Dr. Mark Widdowson, professor and department head at Virginia Tech's Charles E. Via Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering.

The groundwater can be in sand, gravel and fractured rock systems, he said. The water comes from precipitation, rain, snow, humidity, etc. The groundwater discharges into rivers, streams and springs, like at the Barton Property.

Widdowson said the only way to find out how private wells could be impacted by a water-intensive industry, like a data center, is to do testing.

"So we know for an absolute fact that when new wells go in, and they are pumped, they will lower water levels in and around that pumping well, and in some cases, can occur even miles away. You'll see impacts. Now it doesn't mean it's a significant impact, but it's a measurable impact,” he said.

But it depends on the features of the aquifer beneath the surface, something scientists can’t see, he said.

Water from public utilities

Water for data centers also comes from public sources.

Pennsylvania American Water (PAW) is the state’s largest water utility provider, serving 2.3 million Pennsylvanians in 38 counties.

Tony Nokovich is vice president of engineering. On Sept. 2, he testified before the Pennsylvania Senate Democratic Policy Commission.

“The large amount of water needed to cool data centers can exert stress on our water distribution infrastructure,” he said, adding that PAW invests $700 million annually in infrastructure upgrades across Pennsylvania.

The summer is when the water company experiences peak demands for residential and non-residential customers.

“The data centers will further increase our summer peaks, requiring water providers like PAW to construct their facilities to satisfy these peaks,” he said during the testimony.

Archbald, in Lackawanna County, has the most data center proposals of any area in the state, according to padatacenterproposals.com. At least two of the five data center developers there have “will serve” letters from PAW.

“Which simply confirms the property is within our certified service territory,” spokesperson Alana Roberts said. “It is not an approval or a commitment to provide or reserve water capacity. Service can only be provided if the developer meets all tariff requirements, including complying with our standards and fully funding any necessary capital improvements.”

Project Gravity will use the same amount of water daily as over 5,000 residents.

Attorney Raymond Rinaldi, who represents the developer, estimates that the campus will need 360,000 gallons of water per day to operate. The average Pennsylvanian uses about 62 gallons of water a day, according to the Pennsylvania Public Utilities Commission.

Pennsylvania American Water said that the utility has the ability to provide the campus with that much water per day, and that it will come from Pennsylvania American Water’s Lake Scranton reservoir, which has the capacity to treat and deliver 33 million gallons of water per day. Roberts said the utility “does not expect any impact on our water supply from the construction of the Archbald 25 Developer LLC’s Project Gravity data center.”

Brooklyn-based Cornell Realty Management LLC is proposing to build Wildcat Ridge, also in the borough. That development also has a will serve letter from PAW.

Wildcat Ridge expects to use 3.3 million gallons of water per day, according to a conditional use application submitted to Archbald Borough. That's the same water usage as over 53,000 Pennsylvanians, according to the Pennsylvania Public Utilities Commission.

However, during a conditional use hearing, project manager Albert Magnotta III said that may not be the final usage number. He also said the developer is researching using treated water from the mine pools below for the campus.

PAW’s Nokovich said in September that "it is important to place data centers in areas where dependable water service is available."

Project Gold and changing plans

1778 Rich Pike LLC displayed new plans for its data center campus in Clifton Twp. during a special supervisors meeting on Jan. 2.

Those plans looked much different than when Project Gold was first introduced in Clifton and Covington in early 2025.

“If you look at the plan as a whole … we sat through numerous public meetings and heard a lot of the concerns, and many of them, almost all of them, are addressed in the various settlement plans and the master plan that have been submitted, and there's still a very extensive public approval process that this project has to go through,” McHugh said.

In Pennsylvania, municipalities must have zoning for all acceptable land uses. Data center project plans start at zoning, and in Lackawanna County, each of the 40 municipalities has its own zoning laws.

Like many communities around the region, neither municipality had zoning laws to regulate the new and quick-moving industry.

A series of meetings have drawn large crowds of anxious residents, worried not just about water but electricity use and other environmental concerns, including air pollution from generators.

Covington Township Supervisors added a zoning amendment in July after a lengthy meeting where more than 30 North Pocono-area residents, landowners and taxpayers spoke out against allowing data centers in the township in areas zoned residential — or, frankly, anywhere, according to many.

Clifton Township Supervisors added a zoning amendment in May to regulate data centers but not before the township’s zoning ordinance was challenged by 1778 Rich Pike LLC for excluding the industry.

After four hearings, which began in late July, and hours of testimony by experts brought forth by the developer, Clifton’s zoning board ruled in November that its zoning laws were not exclusionary -- essentially that a data center could be built in the township under the current zoning laws.

The developer filed an appeal later that month, before the board even issued its final ruling. By law, the zoning hearing board had 40 days to issue its final written decision. On Jan. 2, the township supervisors approved a settlement with the developer to end the zoning issue.

But it’s still not the end of the residents’ battle against 1778’s data center campus. The Clifton settlement was challenged in court by the Clifton Zoning Board, PennFuture on behalf of the Pocono Heritage Land Trust and Barton Brothers and Covington Twp.

During a legal hearing with Lackawanna County Judge Mark Powell on Jan. 27, Covington Twp. Solicitor Joel Wolff said they are working on a similar agreement with the data center developer, which could mean Covington will drop their petition to intervene.

On Friday, Powell reversed course and denied the settlement.

“Although presented as a stipulation by all parties, the Clifton Twp. Zoning Hearing Board was not a signatory to the settlement stipulation and agreement and not heard on the petition to approve the settlement stipulation and agreement,” according to Powell's decision.

Reached Monday, McHugh did not have a comment on the decision.

“As we are still evaluating it,” he said.

Regardless of the settlement, plans have drastically changed for the data center campus since they were first propose, which McHugh credited to the unnamed end user.

"Really, it's a one-of-a-kind type project compared to the other data centers you're seeing across the state,” he said.

The new plans call for:

- Eleven data center buildings, instead of 30 to 35 buildings, spread over multiple campuses

- The developer originally pitched three-story buildings at 120 feet. The buildings’ heights will be 80 feet, which includes 15 feet of roof equipment.

- Many residents raised concerns over the suggestion in the developer’s original plans to use small modular reactors (SMR) for nuclear power at the campuses. “There is no nuclear SMR involved in the site,” McHugh said.

- Sewage will flow through the Covington Twp. Sewer Authority. McHugh said the developer will pay for needed upgrades at the plant.

- PPL will supply power to the data center campuses.

- According to Clifton’s settlement, the buildings must be 100 feet from any property line and 400 feet from existing, occupied residential structures.

'We want it to be protected'

The Barton Family says they manage their land for diversity and the long term health of the ecosystem, Bolognesi said. Areas of the property are logged to help pay for taxes and property maintenance.

The drinking water and water for sinks and showers is from a spring house system, a wooden building constructed over another natural spring on their property. The electricity at the cabin comes from solar panels.

The partnership has a conservation easement with the Pocono Heritage Land Trust, which protects the property if the partnership dissolves.

"We would love to maintain it for the future generations of our family, but regardless of whether we are the stewards, we want it to be protected,” Thatcher Barton said.

He said no one from 1778 Rich Pike LLC has met with the family or any of the people who will be impacted by the development. He said they’re not acting in good faith.

"We look at ecosystems like a commodity that can just be switched around. And that's why it's so easy to destroy them, because some developer can say, ‘oh, we'll just put some over there’ which isn't how ecosystems work,” Thatcher Barton said.

When asked about speaking to neighbors, McHugh said the new plans show that the developer was listening to the residents.

McHugh said 1778 Rich Pike LLC still has to go through a master plan and conditional use process in Covington. If the settlement with Clifton holds up, the next step is a land development submission, which will show the various phases of the buildings and the construction sequences.

“There'll be an opportunity to for them to review and critique and comment on the plans, and we'll have the opportunity to review and address those concerns, but we think we've done a pretty significant job in revising and modifying this plan to address a lot of the concerns that have already been raised,” he said.

McHugh said it’s about coming to that middle ground of responsible development, while still having a feasible project.

"We just hope people will take a look at what the kind of end game of this was, and see how it's transformed to what was originally proposed and what would be sought, if we have to, you know, go through a court process on this, and I think it's significantly reduced the impacts of what was compared to what was originally proposed, and addresses a lot of concerns," he said. "I think we look forward to taking this through the full approval process and putting a project together that everybody in Clifton and Covington can be proud of.”

The Barton Family is spread out throughout the East Coast. Walter Barton lives in South Carolina, other members live in New England. They’ve spent countless hours traveling to the North Pocono-area to join their neighbors in Northeast Pennsylvania and speak out at the public meetings in Covington and Clifton townships.

For Bolognesi, Walter Barton, and Thatcher Barton, the property has helped keep the family together.

"And this data center has brought us much closer together in the fight,” Walter Barton said.

WVIA News wants to hear your thoughts

on data centers by taking our

DATA CENTER SURVEY (click here).